Covering: A Conceptual Key to Love and Sacrifice

Article Voiceover

One of the many delightful things about Modern Hebrew is that it is saturated in Biblical quotations and allusion. For instance, I was refreshing my mind on the statutes surrounding the Day of Atonement in Leviticus 16, and two fairly common slang terms in Modern Hebrew popped out.

The first is if you annoy your Israeli friend, she is likely to tell you to “ללכת לעזאזל”—literally: “Go to Azazel.” (The English equivalent being “Go to hell.”)

The second slang word, though not directly found in the passage, is כפרה. Pronounced “ka-PA-ra,” it is a term of endearment used for even the most casual of acquaintances. Literally, it means “atonement,” implying that the speaker would die for you or their love for you is so great that it covers your sins. With such an intense meaning, you would think it would be reserved for only the most intimate relationships. Instead, the closest equivalent to using “kapara” my eccentric brain can come up with is a British shopkeeper handing you your bag and saying, “There you go, love.”

A cultural note: To Americans, it can seem strange when Israelis, or even British shopkeepers, apply pet names to almost total strangers. To illustrate the socially acceptable way this happens in daily life, let me give you an example from yesterday. I went grocery shopping at a new store and didn’t realize I needed to show the guard my receipt when I left. As I walked away, I heard behind me, “Oi gaveret! Mami! Kapara!” (Hey miss! Dear! Love!) I turned around, and sure enough, the guard was calling after me to come back and show him the heshbon. Another example is former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu congratulating Netta on winning Eurovision, saying, “Kapara alaich,” that is, “Atonement on you.”

Because the term “kapara” is ubiquitous in Modern Hebrew, it keeps the idea of atonement fresh in my mind and gives it an affectionate connotation. Don’t change the spelling, but merely shift the emphasis from “ka-PA-ra” to “ka-pa-RA,” and you switch from the term of endearment to the more religious concept of atonement, with its sacrifice and propitiation. Is it possible that there is a conceptual link between the two seemingly disparate definitions?

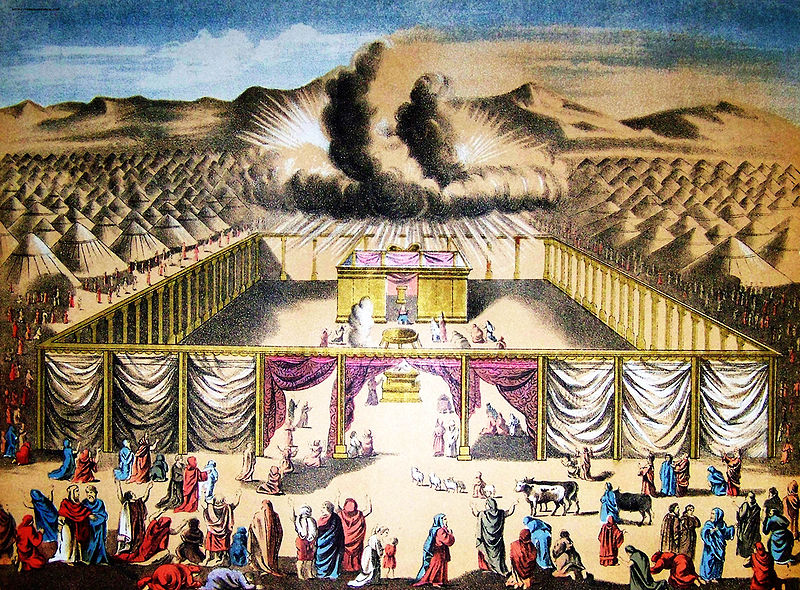

Careful readers will also see that “kapara” (כפרה) and “kippur” (כפור) have the same root: k-p-r (כ-פ-ר). This root carries with the connotation of “covering.” Noah covered the ark with “kofer” (כפר) that is, pitch. (Genesis 6:14) The mercy seat in the Holy of Holies is the kapporet (כפרת), so called because it was the golden covering of the Ark of the Covenant.

In most cases of kapara in the Bible, the Priest, as a representative or an individual, makes atonement for sin or impurity, and then the wronged party (usually God) forgives. The idea of pardon and forgiveness is related, certainly, but distinct from the act of “making atonement.”

For instance, when Jacob knows he is about to meet Esau, against whom he has sinned, he comes up with a plan, thinking, “I may appease him (akhappera fanav) with the present that goes ahead of me, and afterward I shall see his face. Perhaps he will accept me.” Genesis 32:20

But sometimes, there is nothing to be done to appease for the sin. When the people of Israel commit idolatry by worshiping the Golden Calf, Moses tells them, “You have sinned a great sin. And now I will go up to the LORD; perhaps I can make atonement (כפר) for your sin.”

So far, so normal. There is an intermediary for the grieved party to make atonement for the broken relationship. Moses begins by frankly confessing what the people have done. “Alas, this people has sinned a great sin. They have made for themselves gods of gold. But now, if you will forgive (נשא) their sin—but if not, please blot me out of your book that you have written.” (Exodus 32:30-32)

The word translated as “forgive” in English is actually not the word for forgive in Hebrew. “Nasa” (נשא) actually means “to bear or carry.” Moses is not sending gifts ahead as Jacob did nor bringing a sacrifice as the High Priest would later in observance of Yom Kippur. Instead of attempting appeasement for the broken covenant, Moses instead asks God to “bear” the people’s sins. If God cannot bear their sins, then Moses, as well as the people of Israel, are doomed.

God both atoning and forgiving—bearing with a rebellious people—was attributed to his compassion, loving-kindness, and faithfulness to his covenant. (Numbers 14:18-19, Psalm 78:38) The prophet Ezekiel makes the connection between covenant and atonement clear, “For thus says the Lord GOD: I will deal with you as you have done, you who have despised the oath in breaking the covenant, yet I will remember my covenant with you in the days of your youth, and I will establish for you an everlasting covenant. ….I will establish my covenant with you, and you shall know that I am the LORD, that you may remember and be confounded, and never open your mouth again because of your shame, when I atone for you for all that you have done, declares the Lord GOD.” (Ezekiel 16:59-63)

So we can see that when the Lord is both atoner and forgiver, when he is High Priest and sacrifice and the sinned against, that is where kaPAra and kapaRA, love and sacrifice, meet. It for the sake of covenant that the Lord bears the sins of his beloved Israel, covers them in his mercy, and establishes himself as the atonement once and for all.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Dear Devon,

Another great article!

Your words and writing brought a surge of worship in my heart to God! So faithful to his covenant, so full of mercy and compassion!