A Reading of Proverbs 31:10-31

Article Voiceover

After taking a very informal poll of my female friends, both Christian and Jewish, the “Proverbs 31 woman” or the “eishet chayil” (woman of valor) praised in Proverbs 31:10-31 is met with mixed feelings at best. Who is this woman? Jewish husbands sing this acrostic poem over their wives as a blessing every Shabbat, and what evangelical women’s retreat would be complete without a teaching on this ubiquitous passage? She is everywhere, and low-level resentment follows in her wake.

But how has this woman of valor become such baggage to the population she is meant to praise? The eishet chayil’s life sounds completely exhausting and out of reach to many women. If she is an ideal of godly femininity, or the embodiment of Lady Wisdom, or a model of the Church, all of us are found desperately wanting.

And if she is a mere ideal or abstraction, what are we to make of verses such as “Her husband is known in the gates” (v. 23)? Are we to understand that you fall short of this ideal if you are not married to a politically connected man? “Many women have done excellently, but you surpass them all”? (v. 29) If she is an ideal inside King Solomon’s head, of course she will surpass any real woman. It is the ultimate backhanded compliment to the entire female population. It is no small wonder that this passage is fraught with difficulties for its readers.

To be perfectly honest, for the vast majority of my life, I haven’t had any firm opinion about the woman of valor from Proverbs 31. I tend to give a wide berth to any “hot button” topics in the western church, particularly subjects connected with manhood and womanhood. Firstly, I readily admit to not being sufficiently educated to add much to that specific conversation. Secondly, I feel that the attention given to male and female roles should be proportional to the attention that the topic receives scripturally. The recent dialogue around maleness and femaleness seems to have lost all sense of that proportion. Lastly, I hope to value humility and obedience over some need to “assert my rights.” I rather aspire to the Syro-Phoenician woman’s level of faith, which eschews any sense of entitlement. It, therefore, makes me a somewhat reluctant and poor advocate for groups that I am a member of myself.

However, a couple of years ago, I wrote an essay called “Sisterhood of the Serpent-Crushers” about a group of women mentioned in Psalm 68, and it did have a relatively “I-am-woman-hear-me-roar” kind of title. When I saw the essay received as such, I was a bit surprised! It had not been my intention to write an article from a “feminist perspective,” whatever that might be. What had been my intention primarily was to analyze the passage intertextually and secondarily to encourage women with a positive view of ennobled femininity straight out of the Scriptures. We are often told what women are not and what women should not do. This is fair instruction but perhaps not as helpful as it could be if counterbalanced by teachings on what women are and what they should aspire to do.

So, with a bit of fear and trembling, I turn to this eishet chayil passage in hopes that a fresh reading will encourage those who try to untangle the riddles set forth by King Solomon with particular appreciation of one woman’s courage and how women, in particular, might follow her example.

Let the wise hear and increase in learning,

and the one who understands obtain guidance,

to understand a proverb and a saying,

the words of the wise and their riddles. (Proverbs 1:5-6)

Her Children Rise Up and Call Her Blessed

My interest in the woman of valor was piqued when I listened to a teaching on her in light of the book of Ruth and Shavuot (Pentecost). Rabbi David Fohrman gave the talk to a group that had a firm handle on Biblical Hebrew. In his teaching, Rabbi Fohrman was arguing from the text that the eishet chayil of Proverbs 31 was a commentary on the story of Ruth by her great, great-grandson, King Solomon.1This teaching is available on the Aleph Beta platform with a paid subscription. I highly recommend listening!

Now, Rabbi Fohrman is not the first person to make the connection between the woman described in Proverbs 31 to Ruth. The Hebrew phrase “אֵשֶׁת חַֽיִל” (eishet chayil) is only found in one other place in the Scriptures outside the book of Proverbs—in the book of Ruth. In Ruth 3:11, Boaz says to Ruth: “I will do for you all that you ask, for all my fellow townsmen know that you are an eishet chayil.” (Eishet chayil here is translated in the ESV as “worthy woman.”) Also, in the Jewish canon, the book of Ruth immediately follows the book of Proverbs, and the placement is a compelling commentary on the connection between the two stories.

The phrase eishet chayil is rather compelling in its own right. “Eishet” means “woman of” or “wife of” and “chayil”—well, chayil proves not to be such an easy translation as evidenced by its range of the English renderings. (ESV “excellent wife”; NIV “wife of noble character”; NLT “virtuous and capable wife”; KJV “virtuous woman” OJB “woman of valor”) But it was the word “chayil” that first stopped me in my tracks. “What is the word ‘chayil’ in modern Hebrew?” Rabbi Fohrman asked his group. I knew the answer to this question! My mind immediately pulled up the image of an early worksheet from my first Hebrew language class: chayil means “soldier” in modern Hebrew. What a distinctly un-feminine word! How had I never made this connection before? I have sat at numerous Shabbat tables and heard Proverbs 31:10-31 chanted or sung in Hebrew many, many times but never connected the chayil of the Bible to the chayil of modern Israel.

A quick word study of the Biblical Hebrew term chayil finds that the overwhelming connotation (though not the only use, certainly) is martial. My next thought was to check the Septuagint—what term was used in Greek? In Proverbs, the phrase was rendered γυναῖκα ἀνδρείαν—“brave woman” (more literally, “manly woman,” highlighting the contrasting word pairing, though I wouldn’t read too much into it beyond that!) In Ruth, eishet chayil becomes γυνὴ δυνάμεως, that is, “woman of power.”

Those first two words definitely set a tone. Maybe Solomon wishes to portray this woman as a domestic heroine but will change his tune as the poem progresses. However, the very next line (v. 11) puts that hypothesis to rest. “Batach bah lev ba’alah, vshalal lo yechsar.” Batach bah lev ba’alah— the heart of her husband trusts her—sounds lovely and standard. But “vshalal lo yechsar”? The spoils of war/plunder are not lacking?2The sense of loot is strangely lost in most English translations, though “shalal” almost exclusively is used as the spoils of war or ill-gotten gain in the Bible, so I took the liberty of my own translation. We are back to our military metaphor. A few lines down, in verse 15, we have “V’titen teref l’veitah,” or she provides food for her household. The word “teref,” translated in English here as “food,” actually has the sense of prey or a torn animal—more lioness than chef. How had we come from this valorous huntress introduced by King Solomon, who sounds like she just returned from feats of prowess on the battlefield, to the ESV’s “excellent wife”? Perhaps we have fundamentally misunderstood both courage in its feminine sense and what makes an excellent wife. But I digress.

The fierce and feminine aspects of the eishet chayil are not mutually exclusive to King Solomon because he has seen them exemplified in the person of his great-great-grandmother. But is Ruth merely an eishet chayil, one example of female strength well-applied, or is she, in fact, the eishet chayil of her grandson’s poem?

If the poem is about a specific woman such as Ruth, many of the difficulties I mentioned in the introduction would be solved. Not many of us would bat an eye if a grandson said to his grandmother, “Many women have done excellently, but you surpass them all!” What if “Her husband sits at the gates” (v. 23) isn’t a requirement for a godly life but perhaps a detail from this particular woman’s story? “Her children rise up, and call her blessed; Her husband also, and he praises her.” (v. 28) We already know when a husband, Boaz, praised Ruth as an eishet chayil, but what if Proverbs 31:10-31 is fulfilling the first part of that verse, with Ruth’s great-great-grandson rising up and calling her eishet chayil also?

A line-by-line analysis of the eishet chayil poem would yield the richest, most compelling argument that King Solomon is writing an ode to Ruth, but that is well beyond the scope of this article! (Again, I highly recommend Rabbi Fohrman’s teaching!) So, for now, I would like to take just two of the lines from the eishet chayil riddle and treat them as commentary on the story of Ruth for your consideration.

The Kindness of Redemption

בָּֽטַח בָּהּ לֵב בַּעְלָהּ, וְשָׁלָל לֹא יֶחְסָר

Proverbs 31:11

Batach bah lev ba’alah, vshalal lo yechsar.

The heart of her husband trusts in her, and the spoils of war/plunder will not be lacking.

If Proverbs 31:10-31 is talking about Ruth, it would be natural to assume the husband mentioned in verse 11 is Boaz, but that assumption might lead you to miss a key to this riddle. Boaz is not the only husband in the story. Ruth was first married to Mahlon, but he died almost as soon as introduced. What trust could Mahlon have in Ruth? What loot could he enjoy after death?

The key is in the practice of yibum, that is, levirate marriage. For an Israelite man to die childless is a special kind of tragedy because no one can carry forward his family name and inherit his property. His name is in danger of “being blotted out of Israel.” (Deut. 26:6) The law makes provision for this legal conundrum with the practice of yibum, where the brother (a “redeemer”) of the deceased has the option to show kindness to his dead sibling by marrying the widow. Her first born son from that union will inherit the name and property of the first husband.

Yibum is optional and requires a great deal of kindness from the redeemer, who risks muddying the waters of his own legacy by marrying his brother’s wife. The deceased is about as vulnerable as anyone can be—totally helpless and dependent on others to look after his interests, even when it conflicts with their own. Mahlon’s trust in Ruth was fully vindicated when she—a foreigner to the laws of Israel who had more expedient options to secure her future—faithfully searched out a redeemer for her husband’s name. In a way, Mahlon cheated death and was able to “plunder” his legacy, begetting a son from beyond the grave. (With a bit of help from Boaz and Ruth, of course!)

Charm’s Deceptive Power

שֶֽׁקֶר הַחֵן וְהֶֽבֶל הַיֹּֽפִי, אִשָּׁה יִרְאַת יְהֹוָה הִיא תִתְהַלָּל

Proverbs 31:30

Sheker hachein v’hevel hayofi, ishah yir’at adonai hi tithalal.

Charm is a lie, and beauty mere breath; But a woman that fears the LORD, she shall be praised.

Imagine sitting at the dinner table on a Friday night, and your husband is singing “Sheker hachein v’hevel hayofi” over you. That is to say, “Charm is a lie, and beauty mere breath.” As much as I would hope to have my insecurities and vanity under control in this hypothetical moment, I think my feelings would be a tiny bit hurt. If I possess any charm or beauty, I would hope it to be delightful rather than worthless.

But I don’t think that this is primarily what King Solomon means for us to understand from this line. The key is in the word “chein” or charm/grace/favor. It is a word that crops up in the story of Ruth. The first time it appears is in 2:2, when Ruth says to Naomi, “Let me go to the field and glean among the ears of grain after him in whose sight I shall find chein.” Now, according to the laws of Israel, this practice of gleaning was for the “the sojourner, the fatherless, and the widow.” (Deut 24:19) Ruth is all of those things! She is entirely qualified to glean—no favor (chein) required.

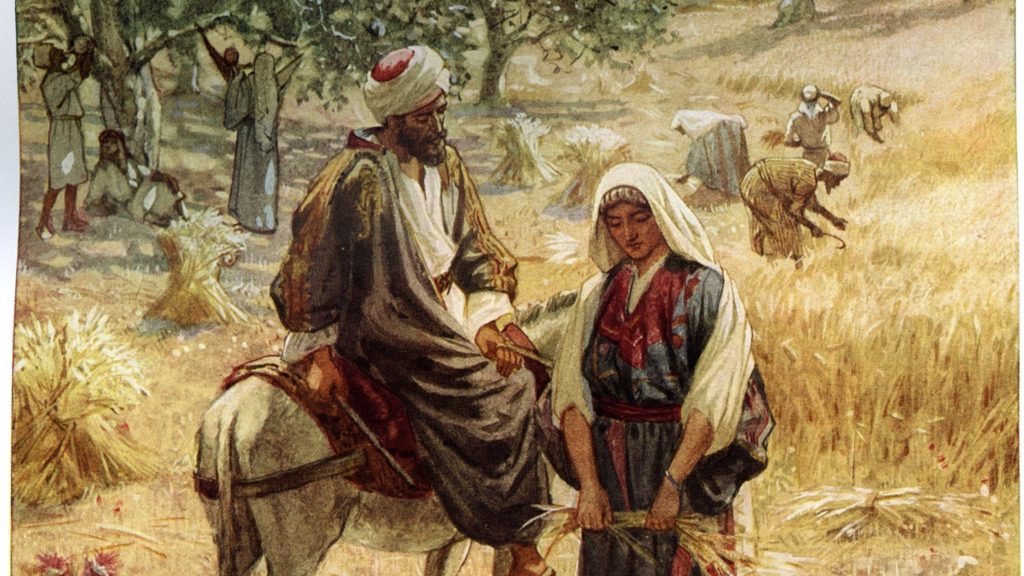

But Ruth has somehow made chein a pre-requisite. When she is well-treated and respected in Boaz’s fields later in chapter 2, she assumes it is because she has found chein in Boaz’s eyes: “Why have I found chein in your eyes, that you should take notice of me, since I am a foreigner/stranger?” (v.10) Boaz gently contradicts her, by saying, “All that you have done for your mother-in-law since the death of your husband has been fully told to me, and how you left your father and mother and your native land and came to a people that you did not know before. The LORD repay you for what you have done, and a full reward be given you by the LORD, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come to take refuge!” (v. 11-12) That is to say, “Charm or favor had nothing to do with how I am treating you! You are not a stranger to me: the power of your selfless acts of kindness and godly devotion show your true nature and deserve support and reward.” Though Boaz can see Ruth’s identity and worth, Ruth still understands herself only as a pretty stranger. She answers, “I have found chein in your eyes, my lord, for you have comforted me and spoken kindly to your servant, though I am not one of your servants.” (v.13) Is chein the only kind of feminine power Ruth understands?

That understanding is put to the test in chapter 3, where it seems we will get a higher-stakes replay of the events of chapter 2. The first time around, Ruth makes a plan to charm the owner of a field so that she will be able to glean food. Naomi approves. This time around, Naomi seems to make a plan not only for Ruth to charm Boaz but to seduce and manipulate him, forcing his hand to redeem Mahlon’s legacy. “Wash therefore and anoint yourself, and put on your cloak and go down to the threshing floor, but do not make yourself known to the man until he has finished eating and drinking. But when he lies down, observe the place where he lies. Then go and uncover his feet and lie down, and he will tell you what to do.” Ruth seems to approve and carries out this plan.

The tension in the story is palpable. Boaz is a descendent of Tamar, who secured her dead husband’s legacy through seduction. Ruth is a descendent of Lot, whose daughters secured their family legacy through manipulating their drunken father and incest. We know from chapter 2 that Ruth has far too high an opinion of the power of chein. Things are not looking good.

The moment of truth arrives when Boaz wakes up and asks, “Who are you?” (v.9) Will the lie of charm prevail? No, thank God! Ruth answers simply and courageously: “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” Ruth understood what Boaz was trying to tell her in the previous chapter: “Charm is a lie, and beauty mere breath; But a woman that fears the LORD, she shall be praised.”

Many Women Have Acted Valorously

Much more can be said about the connections between eishet chayil and Ruth, but I want to end this article with a couple of observations of King Solomon’s conception of womanly courage. Masculine bravery is exemplified by sacrificing one’s own comfort and safety to protect his community, family, and the vulnerable. This often is accomplished through confronting the villains who wish to exploit or harm those “under his wings.” Feminine courage is the same in many respects but worked out in a different arena. Though no less fierce, feminine courage is less about confrontation and more about cooperation. Ruth clung to her mother-in-law. She sought out a redeemer for her dead husband’s legacy. She honored those whose lives were bound to hers with kindness and loyalty. She protected their interests at great expense to herself.

We often mistake feminine power for being rooted in charm, beauty, and seduction. Ruth herself started to make this mistake. But when push came to shove, Ruth chose the better thing: truthfulness and vulnerability. Ruth did not run roughshod over Boaz in her zeal to secure Mahlon’s legacy. She did not attempt to so control the outcome of her plan that the end justified the means. Instead, she honorably presented her plan to Boaz and appealed to his kindness and the blessing of the Lord. Her ability to surrender the sureness of the outcome to protect the dignity of Boaz showed a particular kind of noble strength that leaves charm in the dust.

There is much confusion surrounding what makes a valiant woman or an excellent wife in this day and age. Through the story of his great great grandmother, the wise King Solomon has extracted timeless principles that we would do well to ponder and model today. May we be counted among the many women who have acted valorously!

Footnotes

- 1This teaching is available on the Aleph Beta platform with a paid subscription. I highly recommend listening!

- 2The sense of loot is strangely lost in most English translations, though “shalal” almost exclusively is used as the spoils of war or ill-gotten gain in the Bible, so I took the liberty of my own translation.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

What a great and insightful read. Many blessings dear Devon.